Gerardo Mosquera

When it is said that Latin American and Caribbean culture is the result of a crossbreeding between Europe and pre-Colombian America or Africa, everybody thinks of the ethno cultural fusion above all, while they tend to forget that, at the same time, its formation responded to a historical-cultural hybridization. They insist on a synthesis of different races and cultures, without taking into account the fact that the syncretized cultures were not only different for their particular identity, but also for their degree of historical development.

The origin of Latin American culture, a western and not western one at the same time, was not just caused by an ontological crossbreeding of Europeans, Indians and Africans. It also caused the integration of feudal and capitalist men with men formed in primitive community regimes, as well as in the «Asian mode of production» and other precapitalist ones. Besides, this syncretism at the consciousness level in America adopted archaic methods –slavery, land tenancy system, etc. – that corresponded to former modes of production.

Latin America has been like a time machine, and we Latin Americans are also time mestizos. This has caused that the magical and mythological way of thinking survive in our conscious with significant power that prevailed in our conscious at specific stages of social and economic evolution, and –which is more distinctive- that they formed an organic unit with the western way of thinking that corresponded to Capitalist development. The genetic integration of what is fantastic and “primitve” with what is Cartesian and modern has been the basis of concepts like “the marvelous reality” and “magical realism”. On the other hand, this synthesis has many diverse formulas and proportions, and if we can talk about a general process, it is now at very different stages depending on the case, with native masses that, to a considerable degree, keep their original culture. Thus, America is also a multicultural and “multitemporal” conglomerate.

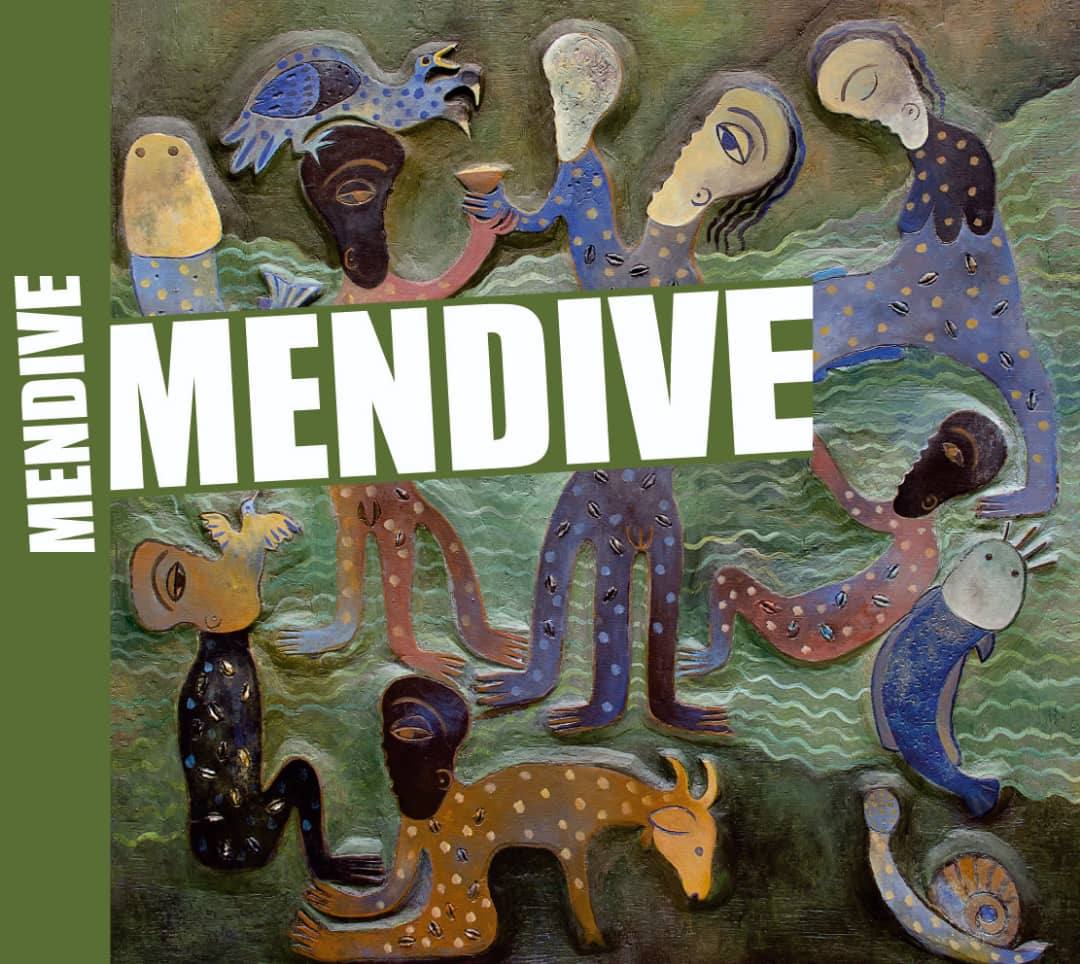

The art of the Cuban Manuel Mendive (Havana, 1944) is a result of this peculiarity. He was brought up in a conservative family in regards to Yoruba traditions –an original culture of the present Nigeria, very influential in Cuba and Brazil- that remained in the Santeria or Ocha’s Rule, an Afro Cuban syncretic cult of which he is a practitioner. At the same time, he graduated from the Fine Arts Academy and studied Art History. We are not in front of a naïf: we are facing a painter that makes use of a “primitive” language within a sensibility that is proper of the western modern art, and with a professional craft to transmit the contents of the magical and mythological “primitivism” of his worldview fully. Only in that respect can we talk about what is “primitive” in his art. That is, not as much from the artistic point of view, as from the artist’s own conscious.

Contrary to what happens in the cases of Wifredo Lam or the sculptor Agustín Cárdenas, the formal influence of African and Afro Cuban visual art in Mendive is just indirectly. In Mendive, there is a use of the basic recourses of “primitive” art, of its structural, narrative and other peculiarities, rather than an iconographic basis. It is about the incorporation of a whole language that expresses a vision of the universe.

Mendive makes use of a living mythological way of thinking as a path to approach a representation of the world and a reflection about man’s general problems. He does it with the typical lack of pretension of many Cubans when they interpret modern life events and issues from a mythological perspective, or when they daily make use of magic to influence them. The painter projects myth towards life, towards reality. That is why his art, besides representing pure Afro Cuban mythology with a sense of universality (for example, in Endoko the sexual intercourse between Changó, god of fire and virility, and Ochún, the Yoruba Venus, is shown as a universal union), involves historical, political, gender, current and other themes, within a mythologizing interpretation. For him, myth only constitutes an artistic method, since it is the application of a system of everyday thought to art. For Mendive, as for a bard of heroic times, mythology is real in all its meaning.

The evolution of his work could be considered as a process of internalization of myth as an artistic means of investigation. It started at the beginning of the 1960s with a very vivid and deep vision of Yoruba origin myths kept in Cuba, in what is still the most valuable artistic moment of his career. It is the «dark stage»: somber works, where painting and sculpture are fused, made with disposable material, medals with trinkets and human hair, burnt with fire or damaged with acid, an impressive look of a real magic object. We could say that by looking at it, we experience an artistic recreation of myth made from the inner part of a mythological magic carrier who is at the same time a modern painter. This, without the slightest sign of folklorism, since his vision transcended the particular aspect of the myth towards its universality scope, in a reflection about life, man and the world… With this unique personality, Mendive was one of the actors of the expressionist line that the best of Cuban visual arts of the second half of that brilliant decade expressed itself, together with Servando Cabrera Moreno, Chago Armada, Antonia Eiriz, Raúl Martínez and Umberto Peña.

Since 1968, this orthodoxy begins to collapse and the “clear stage” emerges decline of sculptures and collages in favor of painting, color explosion, stylization and sweetening.

yth is open to historic facts, everyday life, national customs and current political events, thus following the general tendency of the 1970s in Cuba. However, in Mendive’s case this is about an organic development of his creative axis and not a forced adaptation to the requirements of time, which was a significant cause of Cuban art and literature flatness at that time. Some of his works of the 1970s are among the most valuable of that decade just because they are not typical of that period. Unfortunately, after that moment, his painting begins to lose meaning and falls into a sweetened decorativeness that will remain until the 1980s.

Trips to the USSR and Bulgaria in 1981-1982, motivate the beginning of a transition In those paintings, Mendive applied his artistic vision to sceneries of these countries without any contradiction, incorporating some local legendary beings and proving once again that his painting was not the result of myth as a theme, but also as a method, or I would be more accurate, as a global mode of an acting world view in artistic creation, everyday life and existential orientation.

After his trips to Africa in 1982 and 1983, a new phase is open. A fantasy overflow occurs that leads him to an unrestrained creation of fabulous beings not taken from or inspired on any myth, but which are creatures of his personal imagination. The fabling agitation comes along with certain baroque style that softens the rather static aspect of his designs, endowing them until today with greater proliferation, dynamism and complexity without breaking that organizing construction that characterizes them.

The formal changes include a growing taste for low key and ground tones, and derive today to the use of chiaroscuro, transparency and other more “pictorial” recourses that break away from flat colors and almost emblematic dotting of his style. It starts like a will to get away from what might become decorative and commercial, in search of a more dramatic painting that emphasizes the expressionist component. Nevertheless, he keeps his unmistakable drawing and images.

In this new stage that ends around 1984-1985, both gods and specific references to everyday life, history or current events have disappeared. These are more general and more abstract images. Mendive likes to say that he presents life, and this is the most accurate statement that can be said. His painting is a metaphor of the essential forces of the world, an anthropomorphous world where man is not the leading center yet, but an element of an order of nature. A “living nature” -as Fernando Ortiz stated regarding Wifredo Lam- in which everything is animated in the most literal of meanings. We face an animist and mythological vision of reality with mystic purposes, in which this is interpreted as a system that guarantees the balanced transformation of everything that exists. Men, animals, plants and mountains participate one another, lose their taxonomy by mixing themselves in a kind of vital continuum. More than elements, they are functions of a cosmos that devour, love, communicate and give birth, in a chain that establishes the universal balance. As Robert Knafo assessed, “phantasmagoric ecology”.

Myth has disappeared as an anecdotic basis, but has developed itself as a methodological foundation. Now it is “underneath”, making Mendive’s fantasy projection easier, a systematic imagination in spite of its exuberance. That is why it is not just this painting narrative character what recalls the Nigerian Amos Tutuola’s novels, which are a lineal succession of actions with fantastic beings that are closely related to Yoruba folkloric tales, and not to religious myths. Several painters of the Oshogbo School have also given a free rein to fables originated in verbally transmitted tales through personal artistic expression. This seems to be a trend common to many modern African artists without academic studies.

Of course, I am just referring to a similarity that can have its oblique cultural bases. Mendive is a professional, but of popular origin, formed in a conservative environment of African traditions, and an artist that neither in his work nor in his personal life has broken away from popular culture. Now he creates his own myths, instead of following the traditional ones, but the former have their roots in the latter, and they are the result of the mythological way of thinking, of a living, a familiar and interiorized mythogenesis. Mendive is not an African in America: his very Cuban painting expresses the complex Caribbean synthesis, its ethno cultural and time mixture. This fusion has occurred in Cuba on a greater degree than in other countries, where the multiplicity sung by Dobrú, the Surinamese poet prevails more: “A tree/so many leaves/a tree”. However, in Mendive’s art, the African source is very strong, especially the Yoruba values, and this can result in transatlantic connections.

Mendive is now involved in interdisciplinary works, in which he paints the bodies of dancers and animals. A plastic in movement and sound, a striking mixture of painting, sculpture, dance, music, pantomime, body art, song, sound, ritual, spectacle, performance, parade and procession where again the “cult” and the “popular” are interrelated. One of these works won him a prize at the II Havana Biennial, and he has subsequently presented them in London, Panama and Venice.

Beyond the refreshing morphological bazaar of these creations, when they are achieved, their value lies in transcending the spectacular, encoding a complex message of strange poetry, structured in the same projection of his painting today. Again, there is no literal reference to Afro-Cuban dances, ceremonies or myths: the representation is generalizing, only slightly allusive. The Afro-Cuban is again the foundation on which Mendive develops his talent, and in the use of the batá drums, the Yoruba chant, the gestures and movements of the dancers and musicians, the possible symbolism of the animals that participate… The result is interesting as a show of synthesis, as an ethnocultural fact and as a significant artistic work.

Such boldness, if it does not slip into the carnival that always threatens them, could prove decisive for Mendive’s work, in need of a jolt capable of revitalizing that loose power of his beginnings. In any case, it is an unusual experience of popular communication.

Published in Art in Colombia, Bogota, n. 37, September 1988, pp. 52-55.